Alfred Kubin’s pen-and-ink drawing “Chevalier d’ Eon” belongs to the “mature” phase of his well-known early work, in which a certain softening of the disturbing pictorial motifs of drive, fear, and obsession, which caused a sensation and outrage among his contemporaries around 1900, may be detected. In the process, not only a refinement of his initially caricature-like, then unusually crude style of drawing, which at the time was perceived as ‘primitive’ and provocative, is to be observed, but also a concentration on a few symbolic figures who are greatly symbolic. Mostly they are located in a diffusely delimited space, which Kubin knew how to create by means of a spraying technique he developed with ink rubbed through a sieve. The first high point for this fully developed drawing style was the so-called „Weber“ portfolio of 1903, in which the publisher Hans von Weber published 15 selected sheets by Kubin from 1901 to 1903 in collotype. Here, famous sheets such as “Das Grausen” or “Des Menschen Schicksal” show a similar focusing of the pictorial message on a single figure. On the artistically sovereign level of Kubin’s early work, as represented by the additional sheets of 1903/05 worked with softer ink brushes, the expressiveness of the composition is now completely integrated into the appearance of the figure.

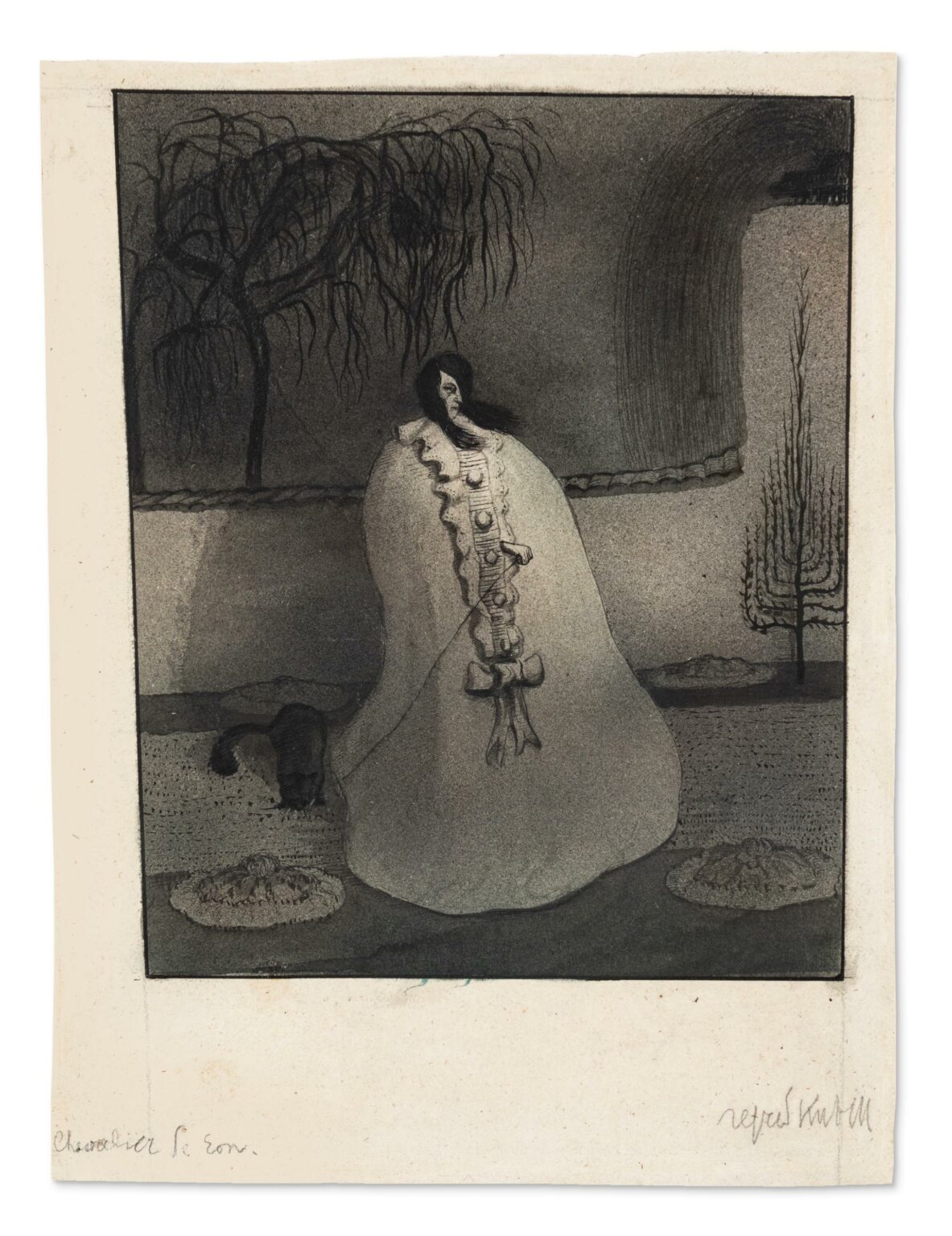

In “Chevalier d’ Eon,” an at first glance masculine figure with long black hair, fully encased in an overly wide, floor-length whitish circumference cape trimmed with eye-catching frilly buttons and bow, stands in front of a park or garden wall. Apart from the face, turned to the viewer with a suspicious and weary sideways glance, only a small, equally finely drawn hand sticks out from the cloak, holding a dark cat beside it on a leash. The cleverly disproportioned figure is centered between two small floral rondelles, with an equally artfully drawn trellis in front of the wall on the right. The tree on the left behind the matte white wall, for whose bare hanging branches Kubin used the soft ink brush and lets them correspond artfully with the sweep of the hair, and the high, tree-crowned break-off on the right edge of the picture shift the depiction completely into the fantastic.

The motif of the “Chevalier” also fits into the discussion of decadence at the beginning of the 20th century, which Kubin addressed in a number of other drawings from his mature early work, such as “Der Gekrönte,” “Der Schwächling,” or “Der letzte König” (The Last King), in part with self-portrait-like features. For Eckhard von Sydow in his extensive publication Kultur der Dekadenz (Culture of Decadence) from 1921, Kubin is the decadent artist par excellence. While comparable works such as those by Félicien Rops still contain the power of indignation, Kubin shows negation: no other draftsman has “made possible and imposed such an intense and concrete awareness of the negative and the decadent” as Kubin.

Kubin’s own handwritten caption is not easy to decipher, but its identification as “Chevalier d’ Eon” only makes the presentation of this remarkable work all the more understandable. The artist was obviously inspired here by the figure of the historical Chevalier d’ Eon (1728-1810), born in Burgundy and in the service of Louis XV as a diplomat, later a political exile in London. Since the 1770s, his gender, not clearly determinable as man or woman, has been vigorously debated and thematized in many prints, many of them satirical. The most striking of these, a book illustration “Mademoiselle de Beaumont or the Chevalier D’ Eon” from 1770 (British Museum, London), divides the figure into two halves, each dressed in a female robe or male rococo suit, with a towering structure with a large curved feather enthroned on the ‘female’ half of the head. Alfred Kubin, who was already a bookworm as a young student and – as he describes in his autobiographical statements and as his library left behind in Zwickledt also shows – devoured ‘offbeat’ literature and picture portfolios, will probably have known this illustration.

In Kubin’s “Chevalier d’Eon”, echoes and overformations of this model seem to be heard not only in the oscillation between the masculine and the feminine, but also, for example, in the large curved tail of the cat, which is reminiscent of the striking feather on the headdress of the “Mademoiselle de Beaumont”.

Dr. Annegret Hoberg

Tuesdays-Fridays 10 am – 4 pm and by appointment

The gallery remains closed on public holidays.

site managed with ARTBUTLER

To enable us to process your enquiry about this work, please note any special questions or requests you may have.